Connecting First Foods and conservation

Conservation Northwest / Jul 19, 2019 / Central Cascades, First Nations, Sagelands

We’re collaborating with Indigenous partners and seeking out opportunities to learn about the role of First Foods in our work.

by Keiko Betcher, communications and outreach Associate

As you’re walking through an old-growth forest or a hillside dotted with sagebrush, you might count dozens of different plants and animals along the way. And for the First Peoples of these landscapes, they might recognize many species as foods their ancestors have hunted and gathered for generations.

Our Indigenous partners from Native American tribes and Canadian First Nations have lived in this region since time immemorial, and they possess a rich, deep-rooted knowledge of the land, often referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). As an organization that conserves wildlife and wildlands in Washington state and southern British Columbia, we recognize that understanding TEK can inform the strongest approaches for success.

As we advance our objectives of Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (JEDI), we’re attending trainings and workshops and engaging in other opportunities to integrate TEK into our work, including at our annual WildLinks Conference, within our Sagelands Heritage Program, and through forest and watershed restoration in the Central Cascades.

First Foods 101

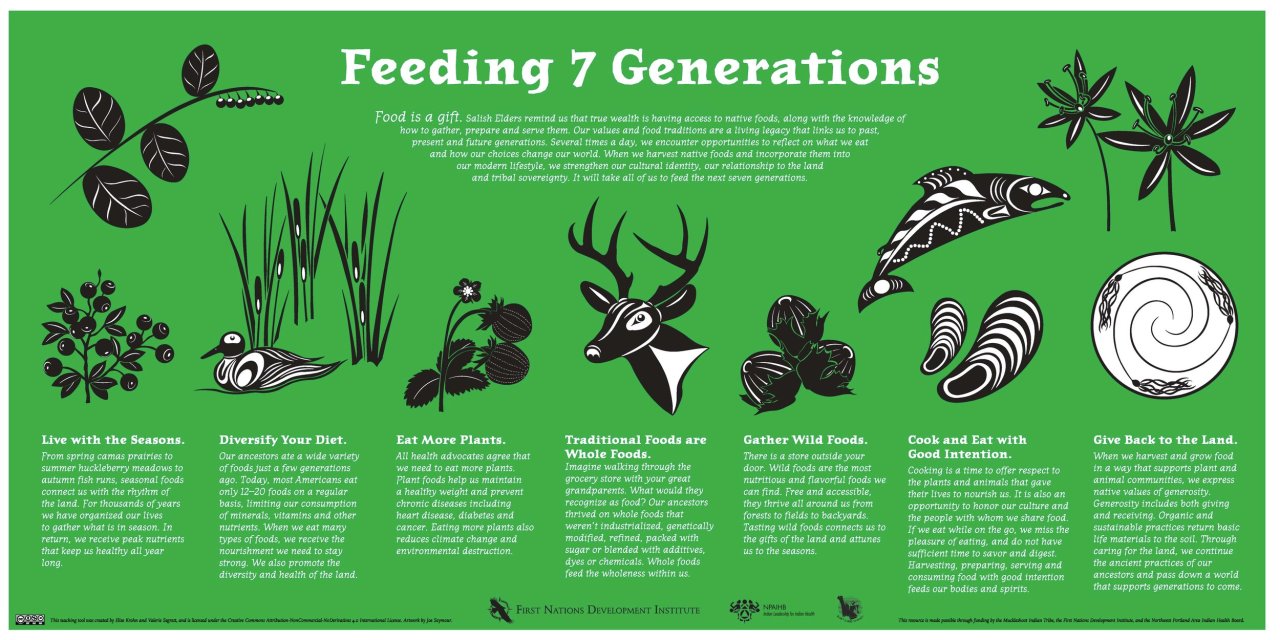

Communicating the full breadth of First Foods is well beyond the scope of this blog, as many foods have their own origin stories and significance unique to a given tribe or indigenous nation. Until recently, TEK has typically not been considered in Western science and approaches to conservation, but for the Indigenous communities the importance of TEK and role of First Foods on the landscape remains significant.

“First Foods are the foods that were eaten pre-contact, and are still eaten now to this day,” said Valerie Segrest, a Native Foods Educator and Muckleshoot tribal member. “They’re foods we’ve organized our lives around for 14,000 years—or as an Elder might say, since time began.”

For the Coast Salish people of Western Washington, Oregon and British Columbia alone, there are more than 300 types of First Foods, from well-known staples like Chinook salmon, wapiti (elk) and camas root, to lesser known species including goose-neck barnacles and eulachon (candlefish, a type of smelt). The Interior Salish and Sahaptin peoples of central British Columbia, the northern Rocky Mountains and central Washington and Oregon’s Columbia Basin have their own First Foods, some of which overlap with coastal peoples, but also inland species such as bison, pronghorn antelope and wapato (a type of wild potato).

Across each of these ethnic and linguistic groups, there are important health benefits associated with First Foods, and they’re also vital to sustaining Indigenous cultures.

“Even if we’re present here as humans, our identity leaves when those foods dwindle,” Segrest said.

The reservation of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe is nestled between the Green and White rivers; key areas for our Central Cascades Watersheds Restoration program , which works to connect and restore wildlands from the Alpine Lakes Wilderness to Mount Rainier National Park. In our efforts to restore quality habitat on this landscape, we’re supporting First Foods including elk, huckleberries and several species of salmon. Our staffer Laurel Baum is working with Muckleshoot staff, state and federal agencies, recreation groups and others to restore healthy meadows and open areas of the forest essential for elk, as well as the clean water and healthy streams that wild salmon and trout rely on for spawning and rearing.

First Foods and Conservation

Since the early days of Conservation Northwest, Indigenous peoples have been vital partners in our work. We support Indigenous Rights and Title, including the treaty rights of these sovereign nations.

As we strengthen our relationships with our tribal and First Nations partners, we’re making conscious efforts to educate ourselves on tribal sovereignty, including attending a Treaty Rights 101 training with the Tulalip Tribes (learn more in this handout on supporting Treaty Rights and Tribal Lifeways), and integrating TEK within our program work.

First Foods Symposium

Earlier this year, several Conservation Northwest staffers including myself attended a First Foods Symposium at the University of Washington called The Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ: Indigenous Foods and Ecological Knowledge. We listened to representatives from Indigenous communities from around the world, including the local Jamestown S’klallam Tribe, Makah Tribe and Heiltsuk Nation, as well the Maori of New Zealand, among others.

Despite the differences in each culture—and the tens of thousands of miles between them—the significance of First Foods to their identity was consistent. I learned that First Foods are much more than edible plants and animals for sustenance. They’re essential for creating balance in spiritual, mental, physical and emotional aspects of life.

I felt honored to share a traditional First Foods meal with the presenters and participants, which included elk stew, herring eggs and local vegetables. And I was inspired to learn about the various ways Indigenous communities are reclaiming their food sovereignty, from restoring camas prairies on the Olympic Peninsula to hosting gathering workshops with tribal youth.

Sagelands Heritage Program

One of the priorities in our Sagelands Heritage Program, which works to maintain, restore and connect shrub-steppe landscapes from British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley to south-central Washington’s Horse Heaven Hills, is to integrate First Nations and tribal ecological, cultural and Indigenous-food knowledge and concerns within our program efforts.

“Right now, we’re learning about First Foods from our Indigenous partners, and how our program is related,” said Jay Kehne, Sagelands Program Lead. “We’re learning to blend that into our work.”

In our efforts to restore the portion of the great “Sagebrush Sea” that extends into Eastern Washington, we’re also supporting the native plants and animals that are important First Foods for local tribes, collaborating with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Lower Similkameen Indian Band and others. By restoring riparian areas, we’re supporting blue camas, which grows in damp places, as well as water birch, an important food source for endangered sharp-tailed grouse.

We’re also supporting the recovery of pronghorn antelope, an important First Food for the Yakama Nation, by removing unnecessary fences and connecting sagebrush habitat, as well advocating for further recovery planning. But for the most part, we’re still in the process of understanding First Foods and their role on the landscape, listening to and learning from our Indigenous partners.

“Longstanding cultures have a lot to teach the rest of us,” Kehne said. “We can have all the science in the world, but sometimes a story can carry a lot more meaning. It’s our responsibility to learn that as we press forward with conservation.”

Wildlinks Conference

The Cascadia Partner Forum, of which we are the coordinating organization, also recognizes the importance of First Foods in our region, and has identified it as one of their priority issues. They organize the annual WildLinks Conference, which brings together scientists, conservationists, land managers, agency officials, and tribal and First Nations leaders from the region to share ideas about wildlands and wildlife conservation.

Our most recent WildLinks Conference was focused on fire and First Foods. We heard from Amelia Marchand, a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes and a Conservation Northwest board member, about the relationship between native plants and culture in her community, as well as Bob Rose from the Yakama Nation Fisheries about the Yakama Nation Climate Adaptation Plan.

Read more about including Indigenous priorities at our WildLinks conference!

Supporting First Foods revitalization

Segrest, with the Muckleshoot Tribe, says some of the threats to First Foods include a lack of knowledge and awareness, a loss of land and treaty rights, climate change, environmental toxins, and inaccessibility. To support the revitalization of First Foods, she says, allies can strengthen their understanding of tribal sovereignty and build partnerships to find solutions.

“Rebuilding our food system depends on how we honor old-world knowledge,” Segrest said. “The conservation movement is a natural partner. We just need allies.”

At Conservation Northwest, one of our JEDI goals and objectives is being a responsible, engaged ally and bolstering our current collaborations. We’re working to achieve that by listening to Indigenous voices and expanding our understanding of conservation to include the wealth of TEK in this region.

It’s a learning process, and we’re eager to incorporate this valuable information into our efforts to protect, connect and restore our wildlands and wildlife. We’ll continue to share updates as we work toward this goal moving forward.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR JEDI GOALS AND OBJECTIVES, OR FIND MORE RESOURCES ABOUT FIRST FOODS.